The 10 Rules of Personal Documentary Filmmaking (Part One)

Only slightly updated from my original list, still as relevant as ever.

It was April of 2007, and my flight coming home from Hot Docs in Toronto was delayed. I had some time on my hands.

Film programmer and journalist had invited me to speak that night to his NYU Contemporary Documentary class on the subject of the personal documentary. I don’t usually prepare much for these kinds of talks, but just for fun I decided to compile a list of “10 Rules of Personal Documentary Filmmaking.”

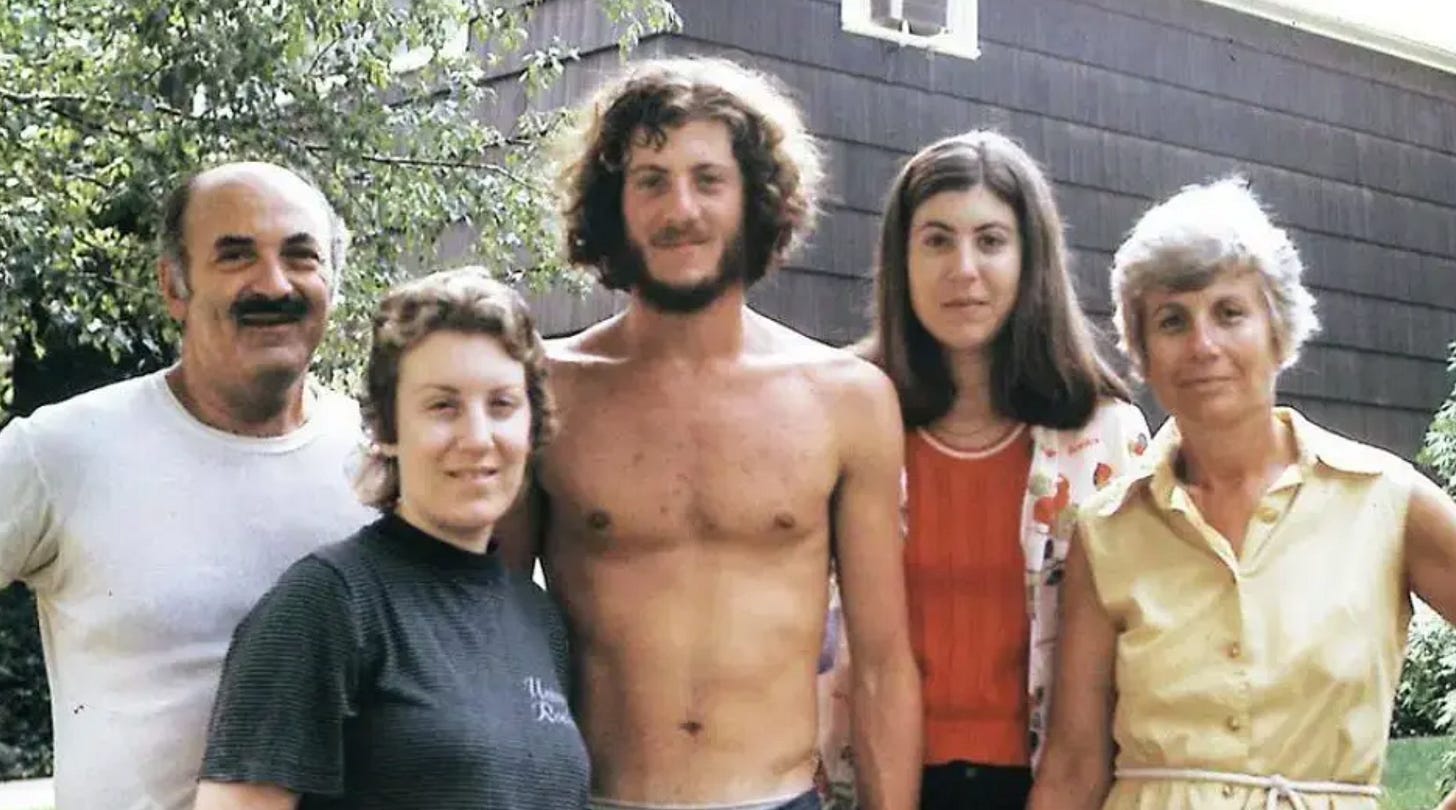

Not that I had 10 rules, exactly. Or even any rules, for that matter. But I did have some strong opinions based on having made a couple of personal docs at that point (Home Page, 51 Birch Street), as well as having helped produce a few I considered stellar examples of the genre (Silverlake Life, Jupiter's Wife and the soon-to-be-released A Walk Into the Sea: Danny Williams and the Warhol Factory).

Normally I would have tossed out these nuggets of wisdom throughout the course of the evening, and they barely would have caused a ripple. But I knew the second I announced I had rules to give the class - 10 rules, no less! - everyone would wake from their slumber, excitedly whip out their notebooks and take down every word. And they did.

My rules have gotten a fair amount of attention over the years (google “personal documentary filmmaking,” it’s the first thing you’ll see). And I think they hold up well. While I’m tempted to update some of the references, I see no need to tweak them too much.

So, drumroll, please… In no particular order of importance, I present my 10 Rules of Personal Documentary Filmmaking. In deference to our busy, attention challenged, easily distractable lives (mine, especially), I’ll post the first five rules now and save the rest for next week.

Go ahead, whip out your notebooks.

The Kids Grow Up (2011)

RULE #1: Don't make it all about you (even though of course it's all about you)

Actually, I lied about the order of importance. This, to me, is the Rule of Rules, the rule every other rule is rolled into. That’s because audiences watch a personal doc with a built-in resistance and even resentment. 1I'm not sure why that is. In virtually every other art form critics and audiences eagerly seek out personal works. Anyone with a reasonably dysfunctional family can pen a best-selling memoir. In the theater, many of our most beloved playwrights (Tennessee Williams, Eugene O'Neill, Neil Simon) write thinly-disguised autobiographies. But for some reason first-person docs are greeted with crossed arms, prove-it-to-me scowls, and an attitude of "who the fuck are you to be putting your life up there on screen?!?"

So the whole art of the personal doc is to appear as if it's not really so much about you. It's about your remote genius of a father who died mysteriously (My Architect). Or your relationship with your mentally ill mom (Tarnation). Or General Sherman's brutal Civil War military campaign (Sherman’s March).

But, in the end, it's really all about you. Your personal journey to enlightenment. And maybe finding a girlfriend, boyfriend or spouse, along the way.

51 Birch Street (2006)

RULE #2: A personal doc is not your personal therapy

Imagine your film playing before a packed audience on a big screen. It's not the place for getting even with nasty ol' mom or dad, believe me. It's not for whining about your rotten childhood. It's not the vehicle for getting the attention you've desperately craved all your life.

Whether it's a personal doc or not, moviegoers want to be entertained, informed and, most of all, enthralled. They want to go along with you on a ride, not see you working through your issues. Spare us, and go see a good shrink, instead. You’ll save a ton of money in the process, too.

112 Weddings (2014)

RULE #3: Don't tell us your feelings, show or indicate your feelings

It's so much more interesting to convey your state of mind through the language of cinema, as opposed to the spoken word. Especially when it comes to narration. In 51 Birch Street, I made it a point to only talk about what was happening storywise in the narration. My feelings were never once referred to.

“After the wedding my father throws us all a curveball. He and Kitty are selling the family home, and in two weeks they'll be moving to Florida. My sisters and I have returned for one last visit to see if there's anything from our past we may want to keep.”

This doesn't mean you don't know what I'm feeling. When you see my dad marry his former secretary so shortly after my mom's death and they lip lock for 12 - count 'em, 12! - seconds at their wedding, do you really need to hear me to say "Yuck"? Isn’t it better to let the audience decide for themselves that this must be profoundly uncomfortable for me and my sisters?

It doesn't mean avoiding emotion, either. Just don't tell us about it. Let it come out organically through the story rather than stating the obvious.

Home Page (1999)

Rule #4: A sense of humor is essential (especially self-deprecating humor)

As I've mentioned previously, for some reason audiences, buyers and critics come to first-person documentaries with a certain "show me" attitude. As in: "Go ahead, dickwad, show me you're an interesting enough person to justify spending 15-20 bucks and the next 90 minutes of my life with!" And they seem to especially get a bug up their butt if the filmmaker appears to take him or herself too seriously.

Therefore, my sense is you have maybe 5 to 10 minutes from the top to establish that you're a relatable human being. And nothing disarms and satisfies viewers more than a well-timed joke or two at your own expense.

Say what you will about Michael Moore but the guy knows how to poke fun at himself. Morgan Spurlock took a little too long getting there for my taste in SuperSize Me (all those factoids about fast food, sheesh!) but he eventually delivered customer satisfaction. And there's a reason why longtime personal doc favorites like Nick Broomfield, Ross McElwee, Judith Helfand and Alan Berliner haven't worn out their welcome. They've mastered the art of self-effacement.

112 Weddings (2014)

Rule #5: Put your story in context

What makes your personal story important to people outside your immediate family? Why would a viewer in France or Japan or Africa find it relevant to their lives? Usually it's because it taps into a much larger, more universal human experience.

If your film is primarily about your family, what might be the larger themes? Is there something about the time period or setting it takes place in that could be further explored? Is there anyone else from outside the main story - experts on the subject, perhaps - that could add more perspective?

With 51 Birch Street, I vividly remember finishing our first rough cut right before the Christmas holiday break. When we returned, editor Amy Seplin and producer Lori Cheatle were adamant that, while the story of my parents worked pretty well, there was something missing that kept it from being more than just an intriguing story. So we turned our attention to the earlier years of their marriage, the 50's and 60's in particular, and to the stifling suburban lifestyle that contributed so much to my mother's unhappiness. It didn't take a huge amount of work to tweak things - an archival clip or two, a few photos, an additional interview. But the effect was profound. When 51 Birch Street went into release, critics considered my parents emblematic of a whole era and the film was compared favorably to the novels of Updike, Cheever and Roth. If they only knew.

You don't necessarily have to know the larger context for your story from the get-go. There are aspects you'll almost certainly discover during the process of shaping the film in the edit room. But it's something you should be mulling from the moment you first decide to make the film, since it informs much of what you'll end up shooting.

Ok, stay tuned for 5 more rules coming next week. In the meantime, do you have your own rules? If so, I’d love to hear them, along with any other comments you might have.

I also recommend you check out Anthony Kaufman’s great Substack. And in case you’re looking for even more rules, here’s: 10 "Rules" of Documentary Filmmaking by Victor Kossakovsky.

Bravo! Please add links to watch your films too

Well written, I love your style of writing, Doug.